In “Croquet: The Complete Guide” (1988) Anton Gill described Reid as “a flamboyant character of the gentleman adventurer type” who was “clearly a skilled player with a vision of democratised croquet”. His vision certainly extended to the prospect of gaining some personal financial advantage from the sport. He was minded to compete with “Monsieur” John Jaques and criticised his products mercilessly. He used the words “absurdity” and “monstrosity” and suggested that Jaques’ patented clips should be flung “behind the fence”. Reid had “acquainted” a Mr Bangs Williams, a New York manufacturer of “croquet things” with his own ideas and he was proud to act as “the herald who proclaimed them”. Mr Williams was presumably grateful but whether he extended any financial recompense is not clear.

In “Croquet: The Complete Guide” (1988) Anton Gill described Reid as “a flamboyant character of the gentleman adventurer type” who was “clearly a skilled player with a vision of democratised croquet”. His vision certainly extended to the prospect of gaining some personal financial advantage from the sport. He was minded to compete with “Monsieur” John Jaques and criticised his products mercilessly. He used the words “absurdity” and “monstrosity” and suggested that Jaques’ patented clips should be flung “behind the fence”. Reid had “acquainted” a Mr Bangs Williams, a New York manufacturer of “croquet things” with his own ideas and he was proud to act as “the herald who proclaimed them”. Mr Williams was presumably grateful but whether he extended any financial recompense is not clear.

The “Captain” (as Reid liked to be known) had a rather striking appearance and was “foppish in his dress”. It is said that he was “addicted to lemon yellow gloves and clothes of unusual patterns and loud checks”. He wore a monocle. This affectation may have given rise to a story that he had a glass eye and that, when he and some of his fellow authors went to places of refreshment, the Captain sometimes had the misfortune to lose his eye in his drink, and “it became necessary for it to be fished out before conversation could be resumed”.

Reid described himself as an “advocate and expounder” of the sport of croquet. In 1863 he wrote a book, simply entitled “Croquet”. Reid described croquet as “an innocent amusement – a game of true civilizing influences”. He expressed the hope that “no class jealousy” would arise to prevent the spread of the sport. It had been “restricted to the lawn of the lordly mansion” but he trusted that it would escape to the “paddock and the village green”.

Northern Irish origins

Thomas Mayne Reid was born into a Scottish-Irish family in Ballyroney, a small village in County Down. He was the son of the Reverend Thomas Mayne Reid, who was a senior clerk of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland. His father wanted him to become a Presbyterian minister and so, in September 1834, Reid enrolled at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution. Although he stayed there for four years, he did not complete his studies or receive a degree.

The Deep South

In December 1839, aged 21, Reid boarded the Dumfriesshire, to make the Atlantic crossing to New Orleans. He arrived in January 1840. Shortly afterwards, he found a job as a clerk for a corn merchant. He stayed in New Orleans for six months. It is said that he left his position for refusing to whip slaves. He later used Louisiana as the setting of one of his best-selling books, an anti-slavery novel entitled The Quadroon (published, in three volumes, in 1856).

From New Orleans, Reid travelled to Tennessee. On a plantation near Nashville, he tutored the children of Dr Peyton Robertson. Twenty years later, he made mid-Tennessee the setting for his novel The Wild Huntress (1861). Following Dr. Robertson’s death, Reid founded a short-lived, private school in Nashville. In 1841 he found work as a clerk for a provisions dealer in Natchitoches, Louisiana. Although he later claimed to have made several trips to the American West during this period, the evidence for such journeys is sketchy. Life in the “wild west” provided the background for many of his novels but whether he experienced this, or merely read the many popular, contemporary accounts, is a matter of conjecture.

Pennsylvania

In late 1842, Reid arrived in Pittsburgh, where he settled briefly and wrote both prose and poetry for the Pittsburgh Morning Chronicle, under the nom de plume, “The Poor Scholar”. His earliest work was a series of epic poems called Scenes in the West Indies.

In early 1843, Reid moved to Philadelphia, where he remained for three years. During this time he worked as a journalist and, from time to time, had poetry published in Godey’s Lady’s Book, Graham’s Magazine, the Ladies National Magazine, using the same pen name. It was in Philadelphia that he met Edgar Allan Poe and the two became drinking companions for a time. Poe later called Reid “a colossal but most picturesque liar”.

Off to war

When the Mexican-American War began in the spring of 1846, Reid was working as a correspondent for the New York Herald in Newport, Rhode Island. On 23 November 1846, aged 28, he joined the First New York Volunteer Infantry, as a Second Lieutenant. In January 1847 the regiment left New York by ship. They camped for several weeks at Lobos Island before taking part in Major General Winfield Scott’s invasion of Central Mexico, which began on 9 March 1847, at Vera Cruz. Using the pseudonym “Ecolier“, Reid was a correspondent for the New York newspaper, Spirit of the Times, which published his “Sketches by a Skirmisher”.

Reid was involved in the victory at the battle of Churubusco on 20 August 1847 and was with his regiment at the storming of Chapultepec, where he was severely wounded in the hip on 13 September 1847, while leading a charge. He was afterwards promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant for bravery in battle. Although he called himself, and is often listed as, “Captain” Reid, his rank is shown, in Heitman’s definitive “Historical Register and Dictionary of the U.S. Army”, only as Lieutenant. It is gratifying to be able to correct Colonel. Prichard in this instance. In his peerless “History of Croquet (1981), he noted that Reid “served in the US Army in the Mexican War in 1846, hence his rank of captain”.

Reid resigned his commission on 5 May 1848. In the winter of 1848-49 he lived (apparently in sin) in the valley of the Mac-o-chee, in Ohio. While there, he wrote Love’s Martyr, his first play, which was performed at the Walnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia, for five nights in October 1848. His “War Life”, (an account of his army service), was published on 27 June 1849. He also wrote “The Rifle Rangers” in Ohio, which was published in 1850.

Return home and a child bride

Reid returned to New York in early 1849 and sailed for Liverpool in June, in the company of a band of volunteers bound for service in the Bavarian revolution. However, rather than accompany these adventurers to the continent, Reid visited his home in Ireland and then settled in London, where he began the production of numerous novels of adventure. “The Scalp Hunters,” his next story, appeared in 1851. There is a suggestion that he may have travelled to the continent to take part in an uprising in Hungary and that, when he reached Paris, he found that the plan had already failed. However, the evidence for this is found in his memoirs, the reliability of which is highly questionable.

In 1853, aged 35, Reid married Elizabeth Hyde, a girl of 15. They moved from London to Gerrard’s Cross, where a child bride was presumably not so obvious.. The publisher Davis Bogue suggested to Reid that he should write books specifically for boys, catering for the Christmas market each year. He wrote a string of successful novels including “The Boy Hunters” (1855). The book was written after Reid accepted that “writing books in which not too many people died, and there was not too much violence, was better business than writing as he did at first”. Reid revealed himself as a keen naturalist and wrote about “the creations of nature”, without all of the moralising and piety in which other, contemporary Victorian authors might well have indulged. He added several other volumes, to his oeuvre during this period.

Croquet

In1863, “Captain” Mayne Reid wrote his book on croquet. It was published by Charles James Skeet of Charing Cross, London. Copies of the first edition of the work are very scarce. In February 2021, a first edition, with “a few light spots, hinges split but firm, otherwise internally very good;” could be acquired from Shapero Rare Books of New Bond Street for £575. So far as Shaperos were aware, there was no other copy available on the market for sale.

When the book entered the public domain in the USA, it was reprinted, as “culturally important”, by Kessinger Publishing as part of their Legacy Reprint Series. It is widely available, via the internet.

In his six chapters, Reid described the words used in the game (“The Slang”); the court (“The Ground”); the equipment (“The Croqueterie”); the positions of the hoops and the pegs (“The Arrangement”); the progress of the play (“The Programme”) and the laws of the game (“The Rules”). He appears to have been delighted by the some of the words used by players. All of the technical words have been carefully and lovingly transcribed by Dr Ian Plummer on his website: www.oxfordcroquet.com.

Literary (and legal) success

It is not immediately obvious why a writer of many “boys adventure stories” should turn his pen to a manual for those interested in playing croquet. The work that he published immediately before his enthusiastic commendation of the contemporary mallet sport, was entitled “The Maroon: A Tale of Voodoo and Obeah” (a form of sorcery practised in the Caribbean). Reid’s interests ranged far and wide.

At this stage of his career, Reid was making a good living from his writing but he was spending inordinate amounts of money on his new home in Gerrard’s Cross, an elaborate reproduction of a Mexican hacienda that he called The Ranche. He wrote “Croquet” there and he undertook some farming on the property. It may reasonably be assumed that he badly needed funds and that he reckoned that a book about the game that had, within a very short time, become extraordinarily popular, particularly amongst the wealthy, might be worthwhile. It is a slim volume and it may not have taken him very long to complete. Furthermore, Reid wrote about almost anything that he experienced in his adventurous life, and about quite a few other things that he probably did not encounter first hand, save in his vivid imagination.

Reid came into some money, as the result of ”Croquet”, fairly quickly. Plagiarism was rife at this time. In 1864, the Earl of Essex published “Croquet” by “An Old Hand”. It was a blatant copy of Reid’s book. The Captain resorted to law, with significant success. All copies of Essex’s book were ordered to be destroyed and Reid was awarded damages of £125 (about £12,000 in today’s terms).

Bankruptcy and return to the USA

Reid had a further six books published in the next two years (including “The Cliff Climbers” (1864) and “The Boy Slaves” (1865). Next came “The Headless Horseman” (published in monthly serialised form during 1865 and 1866 and subsequently published as a book in 1866). This was a story “based on a South Texas folk tale”, featuring, unsurprisingly, an Irish adventurer and hero of the war with Mexico.

Despite his output, in November 1866, Reid was declared bankrupt.

In 1867 he began to publish a daily evening paper, The Little Times. It was a failure. Hoping to recoup his fortune, in October 1867, he and Mrs Reid went to the United States, arriving at Newport, Rhode Island, in November 1867.

In Newport, Reid he wrote “The Child Wife,” which was published by Sheldon & Co. of New York. In their advertisement, the company announced that “Captain Mayne Reid” had “now become an American citizen, and this is the first of his books in the sale of which he has any direct pecuniary interest”. That announcement presumably had something to do with this bankruptcy in England.

Reid wrote many works about American life. In these, he described the colonial policy in the United States, the horrors of slave labour and the lives of American Indians. His many “adventure novels” were, it is said, akin to those written by Robert Louis Stevenson. His books contain action that takes place primarily in places including, but not limited to, the American West, Mexico, South Africa, the Himalayas and Jamaica. He was very prolific. In all, he wrote about 75 books and numerous articles and sketches.

Surprisingly, it appears that Reid was a fervent admirer of Jean-Jaques Rousseau and also a devotee and follower of Lord Byron. He espoused his “liberal, radical and humanitarian ideals”. A renowned orator himself, Reid regularly lectured upon these political subjects. He was a champion of the underdog and many of his novels not only reflect his zeal for the abolition of slavery but also his distaste for authority – especially that exercised by the monarchies and the Roman Catholic Church of his time.

During his second sojourn in the USA, Reid lectured at Steinway Hall in New York (the building housing concert halls and showrooms for Steinway pianos) and his novel “The Helpless Hand” was published in 1868. But in this period in America, things began to go badly wrong. The wound that he had received at Chapultepec started to bother him. A magazine which he started in 1869, called “Onward”, lasted only fourteen months. In 1870 he was confined to St. Luke’s Hospital in New York City for some time, because of an infection of his war wound. On 10 September 1870, he was able to leave the hospital. His wife hated America and, following Reid’s discharge from St. Luke’s, they returned to England, arriving on 22 October 1870.

Home again

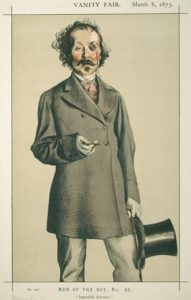

The Captain and Mrs Reid lived in Ross-on-Wye where Reid resumed writing. His work included short stories and revisions of some of his earlier novels. He wrote “The Death Shot” at this time and his work appeared in The Penny Illustrated Paper. In March 1873 he was caricatured as one of the “Men of the Day” in Vanity Fair, subtitled “Impossible Romance”

The Captain and Mrs Reid lived in Ross-on-Wye where Reid resumed writing. His work included short stories and revisions of some of his earlier novels. He wrote “The Death Shot” at this time and his work appeared in The Penny Illustrated Paper. In March 1873 he was caricatured as one of the “Men of the Day” in Vanity Fair, subtitled “Impossible Romance”

By now Reid was very disabled and increasingly depressed and was possibly addicted to opiates. He never revealed how much croquet he actually played but it is reasonable to suppose that the game had, for some time, been more than he could manage. Back in England, he was again hospitalised, this time in Matlock, Derbyshire, at a “water-cure sanatorium”, where he was also treated for “acute melancholia.” In October 1874, an abscess formed on his wounded leg and thereafter he was unable to walk without the aid of crutches.

In 1876, seeking the tranquillity of rural life, he and his wife moved to a small farm near Pontshill in Herefordshire, on the border of the Forest of Dean. They lived there for 7 years. Enamoured of the countryside and particularly keen on the people of the Forest, Reid travelled the area in a pony and trap, often driving 30 miles in a day. As a keen naturalist, he made copious notes on the flora and fauna and he spent time in getting to know the people of the Forest and the Wye Valley. On his many trips into the Forest, just four miles from his home, he often passed the remains of the ruined castle at Ruardean. When he discovered that the beautifully situated building was razed during the Civil War, he began to formulate “the intricate and exciting romance that became his last novel, “No Quarter!” Mr Doug McLean, a local publisher and founder of “The Forest Bookshop”, republished “No Quarter!”, in 2011.

On 26 May 1876, the Birmingham Daily Post, reported that Mayne Reid was then one of the most popular of authors in the country, with “some half dozen of his novels having been translated and printed in from 3,000 to 4,000 copies”. Many of his novels were also serialised in publications throughout the UK, one example being “Gwen Wynn, A Romance of the Wye” (1877), which was serialised in 10 provincial newspapers, including the Sheffield Independent.

From 6 April 1881, for ten months, Reid was joint editor, with John Latey, of The Boys’ Illustrated News. He wrote “The Lost Mountain; a Tale of Sonora” for that publication. At about this time, Reid’s invention began to desert him and he became less popular. However, “No Quarter!” is remembered fondly by some critics. According to Mr McLean, “the tale romps around and through the Forest into Gloucester, to Bristol and back to the Forest. It is a tale of heroes who are the Foresters and the Parliamentarians, and of his arch-villain Prince Rupert, commander of the royalist cavalry”.

Decline and Fall

Reid’s decline into obscurity is puzzling to his admirers. Mr McLean suggests that his radical politics did not endear him to the imperialist influencers of the late 19th century or that his once popular, pioneering ‘ripping yarn’ style of writing had run its course. His views and his literary genre may simply have fallen out of fashion with a new generation of increasingly educated late-Victorians, whose tastes were different.

Reid had been very popular around the world. In his autobiography, President Teddy Roosevelt credited him as a major early inspiration. Russell Miller, in his biography of Arthur Conan Doyle, said that Mayne Reid was one of Conan Doyle’s favourite childhood authors and a great influence on his writings. His tales of the American West captivated children everywhere, including Europe and Russia. Anton Chekhov mentions him in his “Island, a Journey to Sakhalin” (1894). Vladimir Nabokov recalled “The Headless Horseman” as a favourite adventure novel of his childhood years. Czeslaw Milosz, the Polish-American poet and diplomat, who won the 1980 Nobel Prize for Literature, cited Russian translations of Reid as well-remembered early reading material. A chapter on Reid appears in his Emperor of the Earth (1976) collection of essays. D.H. Lawrence has Henry Grenfel, his main character in “The Fox”, reading “a Captain Mayne Reid.”

In 1883 Reid moved to Maida Hill, the fashionable area to the west of St John’s Wood in London, because of his declining health. His last novel, “No Quarter!” and his last boys’ book, “The Land of Fire,” were published after his death, aged 65, on 22 October 1883.

He is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

by John Reddish